CHICAGO – When the discovery of more than two dozen bodies stashed under John Wayne Gacy’s house near Chicago was making headlines all over the world in the late 1970s, Francis Wayne Alexander’s family in North Carolina didn’t think much of it. The way they saw it, Alexander had cut off communication with them because he wanted to be left alone.

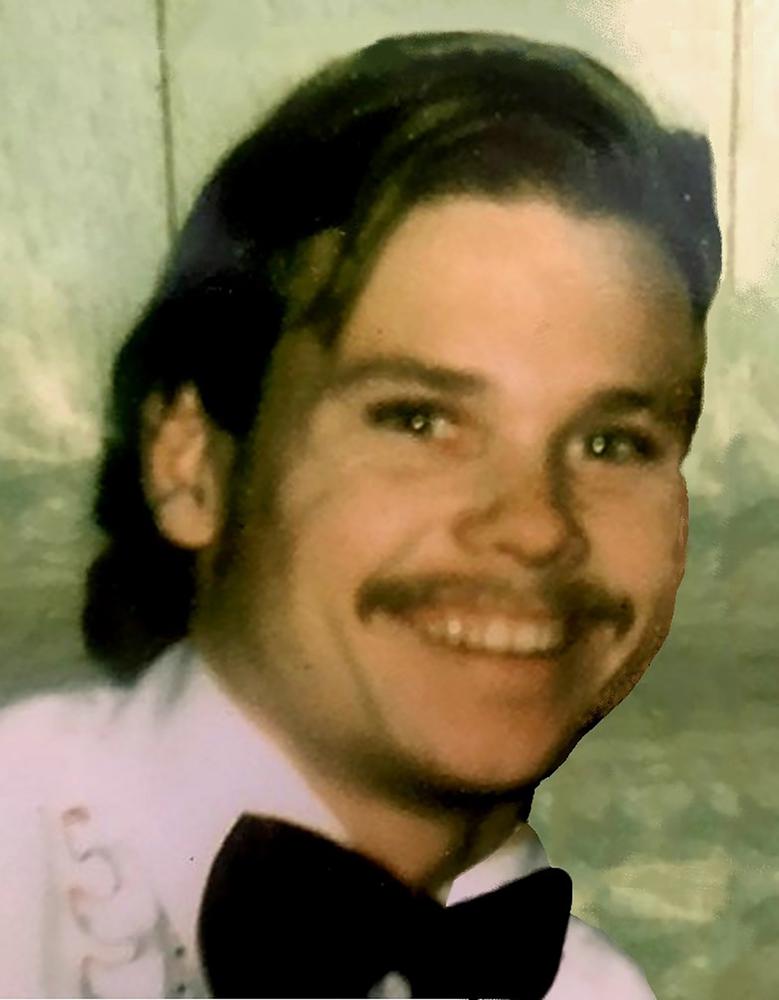

Then came news this month that for more than 40 years, the man they knew as Wayne was known as Victim #5 in the city where he had gone to start a new life. They were told that DNA tests on the remains of one of the half-dozen unidentified victims of the notorious serial killer were Alexander’s.

“They just loved him, but they thought that he wanted nothing more to do with them, so that’s why there was never a missing person’s report,” Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart said at a news conference Monday announcing the latest victim identification.

Though Dart said Alexander’s mother and other relatives didn’t want to speak publicly about his identification as a Gacy victim, Alexander’s sister, Carolyn Sanders, made clear that the family never stopped thinking of what might have become of him.

“It is hard, even 45 years later, to know the fate of our beloved Wayne,” Sanders wrote in a statement released by Dart’s office. “He was killed at the hands of a vile and evil man. Our hearts are heavy, and our sympathies go out to the other victims’ families. … We can now lay to rest what happened and move forward by honoring Wayne.”

Alexander’s remains were among 26 sets that police found in the crawl space under Gacy’s home just outside the city. Three other victims were found buried on Gacy’s property and another four people whom Gacy admitted killing were found in waterways south of Chicago.

Eight victims, including Alexander, were buried before police could determine who they were. But Dart’s office exhumed the eight sets of remains in 2011 and called on anyone who had a male relative disappear in the Chicago area in the 1970s, when Gacy was trolling for victims, to submit DNA.

Within weeks, the sheriff’s office announced that it had identified one set of remains as those of William Bundy, a 19-year-old construction worker. In 2017, it identified a second set as those of 16-year-old Jimmy Haakenson, who disappeared after he phoned his mother in Minnesota and told her that he was in Chicago.

Dart and Lt. Jason Moran shared what they knew about Alexander. Born in North Carolina, he moved to New York, where he was married, and then on to Chicago in 1975, where he soon divorced.

The last known records of Alexander’s life were traffic tickets he received, the last of which came in January 1976. Unlike many victims who were lured to Gacy’s home with the promise that he’d get them construction work, Alexander worked in bars and clubs and there was no record of him working in construction or having made contact with Gacy.

But Alexander did live in an area that Gacy frequented and that was where some Gacy’s other victims had lived, including Bundy.

Unlike with Bundy and Haakenson, who were identified because family members heeded Dart’s 2011 call for the public to submit DNA, Alexander was identified through a partnership between the sheriff’s office and the DNA Doe Project. The nonprofit compared Victim #5′s DNA profile to profiles on a genealogy website to find potential relatives. That led it to Alexander’s family, and Alexander’s mother and half-brother provided their DNA for comparison.

Between the genetic testing, financial records, post-mortem reports and other information, investigators were able to confirm that the remains were Alexander’s. They were able to get a general sense of when he was killed because they knew when the victim who was buried on top of him went missing.

Dart and Moran said the department might be able to use the method used to identify Alexander to identify scores of other people in the county who died and were buried anonymously.

“This is one of the newest investigative tools for investigations of missing and unidentified persons,” Moran said.

Dart declined to give Alexander’s hometown, saying the family hasn’t said if it wants to bring his remains to North Carolina or keep them where they’ve been buried for all these years. But in its news release, the sheriff’s office did thank the police department in Erwin, about 35 miles (56 kilometers) south of Raleigh, for its help.

The submission of DNA from people who suspected Gacy might have killed their loved ones has helped police solve at least 11 cold cases of homicides that had nothing to do with Gacy, who was executed in 1994. It has also helped families find loved ones who while missing, were alive, including a man in Oregon who had no idea his family was looking for him.